By Doug Marman

The main premise of the Lenses of Perception theory is that there are fundamental lenses—ways of seeing—and we can only perceive through one lens at a time. A recent series of experiments validates this idea.

Researchers from Case Western University and Babson College published a study three weeks ago titled, Why Do You Believe in God? Relationships between Religious Belief, Analytic Thinking, Mentalizing and Moral Concern.

Their test results show that when people think of religious matters, their brains suppress critical thinking. And when they focus on scientific topics, their brain suppresses religious thoughts.

“It suggests religious beliefs and scientific thinking clash because different brain areas are involved in both cognitive processes.”[1]

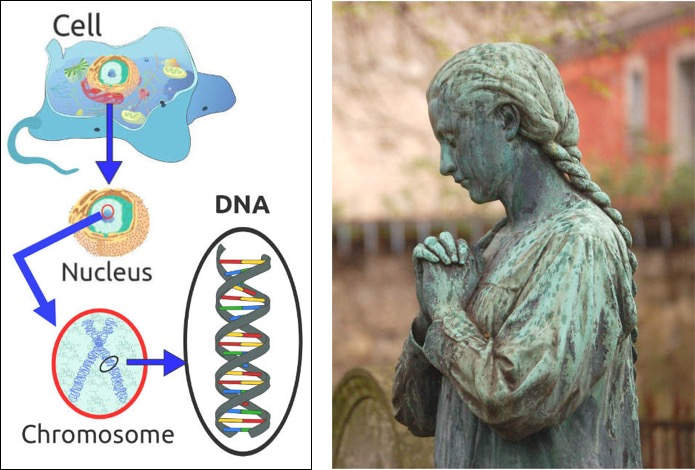

Thinking about science and thinking about religion require two different brain networks, and both networks suppress the other. (“Say your prayer” photo by Joachim Bär. Eucaryote cell illustration from Wikipedia.)

In other words, the experiments showed clearly that working with science involves one brain network, while religion works with a completely different network. And the two networks interfere with the other, making it hard to use both at the same time.

The fact that these brain networks clash with each other is one reason we see conflicts between religious belief and science. However, lenses of perception theory suggests that this isn’t the underlying cause.

Our brains evolved these two networks for a reason: The world is governed by different ways of seeing. This isn’t just about the lenses that human beings use. It reaches all the way down to the level of subatomic particles.

Everything works this way because the world isn’t created by outer forces. It comes into existence through conscious experiences, at every level. That’s why perception plays such an important role.

For example, the scientific perspective uses a third-person lens. That’s the lens we use when looking at the world as if we’re outside observers. This turns out to be the best approach for studying mechanical reactions because particles go along with the outsider perspective. This is why, when trying to analyze a cause-and-effect process, third-person lenses give us the clearest picture of what’s happening.

But the world isn’t just mechanical. Relationships also hold groups together and connect beings to each other. These ties emerge from second-person experiences, created by common interests shared with others.

Second-person perceptions are the basis of all relationships. However, they come in two distinct forms.

First, there is a sense of empathy that allows us to relate one-on-one with another person or animal. We experience this with friends and our pets when we connect with them.

When someone we care about is in pain, we actually feel it. At the subatomic level this is known as entanglement. If two particles become entangled, they literally form an invisible alignment that reaches across time and space. This is one of the many mind-boggling features of quantum physics that make sense when we see them as relationships.

The second type of second-person perception gives us our moralistic sense of the right thing to do. Moral concerns emerge from connections to groups such as communities we belong to, companies we work for, or even our feeling for the human race or the whole of life. Working together with others shows us that we can create something greater as part of a group.

This is where our sense of responsibility comes from. We want to contribute. We want our lives to mean something. I call this the “all-for-one bond,” because it’s a special relationship that team members have with each other when working toward a singular goal.

At the level of fundamental particles, the same force holds atoms together. And in biology, cells bind to the organisms they belong to for the same reason.

So, our brain evolved ways of seeing these patterns of behavior because the world is shaped by these relationships.

The research paper, above, ran tests to see the difference between empathy and moral concern. They wanted to determine how each of these two types of relationship relate to religious belief. Surprisingly, they found that only the moralistic sense showed a strong connection. Empathy played hardly any role at all in the religious experience.

This is exactly what the lenses of perception theory predicts. Religion comes from our sense that there is a higher purpose to life and that a life with meaning comes from working with others for something beyond ourselves. This doesn’t belong to religion alone. Scientists also feel the sense of purpose that comes from working with others for the advancement of science.

This raises another interesting point reported by the above paper: There is no reason why we can’t move back and forth between religion and science, between our moral sense and an analytic perspective. We simply need to learn that they engage two different ways of seeing. Two different brain networks are involved. This means that we need to change lenses when shifting from one to the other.

“The study also points out that some of the great scientists of our times were also very spiritual men. ‘Far from always conflicting with science, under the right circumstances religious belief may positively promote scientific creativity and insight,’ says Tony Jack, lead author of the study. ‘Many of history’s most famous scientists were spiritual or religious. Those noted individuals were intellectually sophisticated enough to see that there is no need for religion and science to come into conflict.’”[2]

[1] http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/critical-thinking-suppressed-brains-people-who-believe-supernatural-1551233

[2] http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/critical-thinking-suppressed-brains-people-who-believe-supernatural-1551233

Perhaps I could summarize the main difference is the interpretations we are drawing from the same Paper. eg Doug says “The point they are making is that moral concern is different from empathy, and the correlation between religious belief and moral concern is high, but non-existent between empathy and religious belief.”

I heard the paper saying that empathic concern is the core part of moral concern and there is correlation between them and religious beliefs. That there is an (undefined) link between mentalizing and empathic concern but there are other ways to come to empathic response or beliefs besides mentalizing about it. Then I think the paper said that there is no link between mentalizing and religious belief. I also think it is a given that mentalizing is not the same as analytic reasoning or thinking mode. I do not know why there is this difference in interpretation. Thanks and good luck with the work.

Thanks for your summary. I just made an attempt to answer this in my reply to your other comments, below. But I’ll add a few more words, since it’s important.

These are issues of semantics. I think we can clear them up by just explaining how we are using these terms.

The key issue here is the word empathy. The paper uses “empathic concern” as another way of saying “moral concern.” They are both involved in the same brain network. They say “empathic concern” to show that people have a feeling to do the right thing. But I don’t view this as empathy, because when I use the word empathy I’m describing the connection that people feel for another individual. I believe this is the most common meaning of the word. This is different from the connection that people feel for society, the whole of humanity, and doing the right thing morally.

These are two distinct ways of connecting to others. They are two different types of relationships that are clearly distinguishable with the right lenses. The authors of the study admit that they don’t know how exactly these two are related, empathy and moral concern, but they do seem to be related. Yes, they are related, since both are based on second-person lenses. That’s why we can describe them both as feelings of connection. But connecting one-on-one with others is different from connecting to a group, and once we see this, it makes the distinction quite clear.

This is a good example of the value in understanding lenses. It can make so many things clear that were once vague. That’s what I was trying to point out with this article. I think this back and forth dialogue has helped a lot to make this point clearer.

So, thank you, and good luck with your work as well.

Doug.

Doug says:

“At the subatomic level this is known as entanglement. If two particles become entangled, they literally form an invisible alignment that reaches across time and space. This is one of the many mind-boggling features of quantum physics that make sense when we see them as relationships.”

and “At the level of fundamental particles, the same force holds atoms together. And in biology, cells bind to the organisms they belong to for the same reason.”

I am unaware of any proven or logical correlation between the theoretical workings in quantum physics of sub-atomic particles and regular human psychology, neuroscience, and interpersonal relationships. I think that is a stretch. It looks like a category error to me. It may be a fun way to hypothetically discuss things metaphorically but I think it is unwise to assume this is actually how it happens in the real world.

If this is true about ‘science’ and analytical thinking: “The problem is that it has a flaw that limits our perceptions.”

from https://lensesofperception.com/2016/03/the-lens-of-science-and-its-flaw/

Then it is equally true about religious beliefs and thinking:- The problem is that it has a flaw that limits our perceptions.

Another example about Newton’s Laws: “What happens when a tool is used so often that it becomes common? It strongly shapes our way of seeing the world. And this is exactly what happened, since everywhere we look today we see causation at work.”

And what about Moses’ Law, Mohammed and Jesus’ Laws? Hindu and Buddhist Laws? Mormon and Catholic Laws? Scientology’s spiritual and psychological Laws?

Well, what happens when a tool is used so often that it becomes common? It strongly shapes our way of seeing the world. And this is exactly what happened, since everywhere we look today we see … religious beliefs and thinking … at work.”

If we have been born with the hard wiring to adopt and move between at least two kinds of cognitive thinking and default personal emphasis on one not the other, then surely both options were meant to be used equally even if only one at a time?

Yes seems the most likely answer to me. Two legs both carry the body’s weight equally. It follows that the two ways of thinking both need to carry an equal weight of thinking in making judgments about our choices and life in general. I do not think there is a simplistic one, two or third way of seeing or thinking. The potential options are endless. The wise don’t restrict themselves to predominantly only one way.

Thanks for your comments. First, about your comment that you are unaware of any logical correlation between quantum physics and human level relationships or neuroscience.

I go into this in depth in my new book, Lenses of Perception. This web site discusses the ramifications of the information presented in that book.

Yes, there is a logical correlation, but it isn’t one that I’ve heard discussed anywhere else either, so I’m not surprised that you haven’t heard of it before.

In the book, I show that it is possible to understand the bizarre behavior of subatomic particles. The approach I take is consistent with the mathematical formalism of quantum theory. It is closely aligned with the Transactional Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics, especially Ruth Kastner’s interpretation.

However, the conclusion that this new approach arrives at is controversial, since it says that unpredictable human level behavior is not only similar to the unpredictable nature of quantum particles, it is directly related by the same underlying principles.

The book includes extensive examples to show that this correlation holds at the human level. In other words, the idea that quantum behavior is limited to subatomic particles is wrong. It is limited to the level of individuals. Once one gets to the level of masses of individuals, then the quantum effect disappears and is replaced by Newtonian types of cause and effect forces.

Next, you point out that if the scientific lens has a flaw, then this is equally true about the religious belief and thinking. I agree with you completely, and this is exactly the same point I make in my book. In fact, that is the point I’m making in this article: That no single lens is enough. We gain a deeper insight into the truth by using multiple lenses.

You are right to point out the flaw in religious thinking that leads people to try seeing everything from one lens. The same is true with science, but my point is that it isn’t necessary to limit ourselves to one lens. We can expand the scope of science and religion by using multiple lenses. This not only helps to build a bridge between the two, but it also helps solve many of the puzzles that have stumped scientists and religion.

You ask if we are born hard-wired this way, then shouldn’t we use these two lenses equally, if only one at a time? Yes. The point I’m making in this article, however, is that the reason we can only use one at a time is that this is the nature of lenses.

The brain isn’t causing this. The brain has evolved this way because this is the nature of perception.

But there is another important point here: We can only look through one lens at a time, but there is a huge added insight gained from going back and forth between lenses. It offers a more complete understanding because it gives us added context.

You said: “The wise don’t restrict themselves to predominantly only one way.”

That’s exactly the same point I make in my book, Lenses of Perception. We keep trying to find one lens that can explain everything, but this is a mistake.

I agree with you completely on this. In fact, from what you say above, it sounds as if we might be closer on these things than you thought.

Thanks for your comments.

Doug.

I may have been a little misunderstood. Doug says: “In fact, that is the point I’m making in this article: That no single lens is enough. We gain a deeper insight into the truth by using multiple lenses.” Yes, of course. I do not think this is a new idea. Studies showing brain activity that indicates separate modes is coming out in all fields so this is not unexpected either.

I believe a better word than ‘flaw’ could be used to indicate all modes of thinking have predetermined limitations and are only fit for purpose.

From the site referenced Wilczek synthesizes the larger truth to which complementarity speaks:

“To address different questions, we must process information in different ways. In important examples, those methods of processing prove to be mutually incompatible. Thus no one approach, however clever, can provide answers to all possible questions. To do full justice to reality, we must engage it from different perspectives. That is the philosophical principle of complementarity. It is a lesson in humility that quantum theory forces to our attention… Complementarity is both a feature of physical reality and a lesson in wisdom.”

https://www.brainpickings.org/2016/05/02/complementarity-frank-wilczek-a-beautiful-question/

When it’s said that “we can only perceive (and think) through one lens at a time”, and there are “fundamental ways of seeing (thinking).” Yes of course I agree and the review paper did confirm this seems to be the mental processes going on.

I am unsure that a lens of science and analytic reasoning are the same thing. While analytic thinking is a important part of science it is not the whole of it. Every scientist is different and has varying approaches.

I’m fairly sure that mentalizing and analytic thinking are not the same things either. I am quite sure the paper indicates that mentalizing and empathic concern are not the same thing. For although they have a connection, Mentalizing is not connected with predicting belief whereas empathic concern and moral concern are.

eg “Mentalizing involves the ability to predict someone else’s behavior based on their belief state. More advanced mentalizing skills involve integrating knowledge about beliefs with knowledge about the emotional impact of those beliefs. Recent research indicates that advanced mentalizing skills may be related to the capacity to empathize with others. However, it is not clear what aspect of mentalizing is most related to empathy.”

http://scan.oxfordjournals.org/content/3/3/204.full

I think this is saying that Mentalizing and Empathy may have connections, but they are two different things. In every study they found that Empathic Concern (IRI-EC), a central aspect of moral concern, significantly predicted religious and spiritual belief.” Mentalizing did not.

The paper says in the abstract: “Using nine different measures of mentalizing, we found no evidence of a relationship between mentalizing and religious or spiritual belief.”

I’m sure we can agree on many things. Good luck with your work. Maybe Wilczek would be interested in your ideas and theory?

I agree with everything you said here, and yes I do think that Wilczek might be interested. And I saw that same quote about Wilcek’s new book when I read that article on Brain Pickings. It’s a great quote, so, once again, thanks for sharing it.

You are right about all of the neuroscience research that has been showing many of these things. I have a chapter on this in my book. Networks in the brain are the latest topic of research, and the study I cited in this article is a good example of it. However, neuroscientists continue to treat these networks as if they are causal drivers when the evidence only shows correlations, not cause and effect relationships.

This is a good example of why I use the word “flaw” and I think it is a good word to use. It isn’t just that the scientific approach is limited. As you say, that isn’t anything new and most scientists realize this.

The real problem is that when you use the “third-person lens” to study objectively, and you do this every day for your work, it forms a subconscious lens that shapes the way you see. If we aren’t aware of what is happening, we can easily start assuming that the objective view is the only one that shows us what is true. And this leads many scientists to treat the brain as the cause of our thinking, genes as the cause of our behavior, that health can be restored by medicine, and quantum events are completely random.

There is some truth in all of these positions, because they represent how it looks from the outside. But that picture is incomplete because there is an inner aspect to all of these issues, as well, that can’t be seen by outsiders. Objectivity doesn’t give us the full story.

In other words, there is indeed a correlation between the brain network that switches on when we are doing analytical thinking, but this doesn’t mean the network is driving this. Once we find a new way of seeing this, it becomes clear that the brain is following, not leading. There are, of course, cases where the brain’s activity affects our moods as well, because the relationship is a two-way street, showing us that cause and effect isn’t what is going on here. More on this in my book.

The fact that so many neuroscientists fall into this way of seeing and conclude that the brain must somehow be creating consciousness shows that they don’t realize it is their use of the third-person lens that is shaping their beliefs and way of seeing. That’s when the limitation in the lens becomes a flaw.

We can see effects of this everywhere in our society, because the scientific lens has become so widespread that we all use it, whether we realize it or not. For example, one of the strangest results of this is fundamentalist religious followers who read The Bible literally and conclude that the world was created 6,000 years ago. They think they are in a battle with the scientific view when they take this position, but in fact their own lens has been shaped by science. That’s where this literal-mindedness comes from. It’s a modern problem. The writer’s of the Old Testament were nowhere nearly as influenced by seeing things literally. To them, truth was something that speaks to you. It’s an inner connection.

That’s why a limitation in a lens, when it is the only lens we use, turns into a flaw. We can’t see how it starts getting in the way of our seeing things as they are.

One last thing that I think might be worth commenting on. Are the lens of science and analytical thinking the same thing? No, not exactly. I believe the brain network they are studying that lights up with analytical thinking is related to the third-person lens. I’ll be writing more about this in the future. You are right that science isn’t limited to this. I also talk about this in my book. Scientists also use first-person lenses, whether they realize it or not. They need to use first-person lenses when running tests to verify their theories. It is this use of two lenses that makes science so useful in finding truth. But it has become accepted to frame all scientific theories in a third-person perspective, so that’s why most scientists view the world this way and discount the inner side of the story.

I agree with you that mentalizing and analytic thinking are not the same and that mentalizing is not the same as empathic concern. This is exactly what I was saying, as you know. You said that the paper sees a connection between empathic concern and mentalizing, but they are different. I agree with you. Here’s the issue: The scientists writing this paper are trying to use objective definitions. That’s why I think the term mentalizing is a poor choice. They are using this word to describe something technical. Here’s what matters: A network in the brain lights up when people consider what other people are thinking about them. This is why I believe they’ve chosen the word mentalizing. By using this term they avoid the subjective experience of empathy that connects people to each other, but it is this connection that makes it different from moral concern. With the right lenses, this becomes much clearer.

I realize that a lot more research is needed to put this all on a solid scientific ground, however, as I study the latest experiments it is easy to see that it explains more and more things so well that it is worth considering. And it changes the picture of the world significantly.

Thanks for the dialogue.

Doug.

Hi, here is a link to the Paper being discussed.

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0149989#abstract0

Abstract quote:

We find that religious belief is robustly positively associated with moral concern (4 measures), and that at least part of the negative association between belief and analytic thinking (2 measures) can be explained by a negative correlation between moral concern and analytic thinking. Using nine different measures of mentalizing, we found no evidence of a relationship between mentalizing and religious or spiritual belief. These findings challenge the theoretical view that religious and spiritual beliefs are linked to the perception of agency, and suggest that gender differences in religious belief can be explained by differences in moral concern. These findings are consistent with the opposing domains hypothesis, according to which brain areas associated with moral concern and analytic thinking are in tension.”

Introduction quotes:

“Whereas analytic thinking discourages religious and spiritual beliefs, there is both theoretical and empirical support for the view that belief is positively linked to social cognition. A number of theorists have argued that the tendency to perceive agency and intentionality encourage belief in supernatural agents. Broadly supporting this view, a number of studies and theories have linked measures of empathy, social cognition, and emotion self-regulation—including measures of social and emotional intelligence—to religious and spiritual belief [8–22]. However, it is now recognized that social cognition can be subdivided into a number of distinct dimensions, both behaviorally and neurologically [23–26]. Hence, it remains to be established which specific dimensions of social cognition are most strongly linked to religious belief.”

“In addition, we have shown that certain moral judgment tasks which hinge on perceptions of moral patiency are impacted by personality characteristics associated with psychopathy (i.e., deficits in empathic concern) but not by individual differences in mentalizing (i.e., deficits in theory of mind) [31]. Based on a review of this work, we identify moral concern as a broad category which includes empathic concern, interpersonal connection, prosocial behavior and aspects of moral reasoning. It is important to note that individuals with high levels of moral concern will not necessarily behave more ethically in all situations. Indeed, some researchers have claimed that high levels of empathic concern can be a detriment to moral behavior [47]. Further, there is empirical support for the view that moral concern for others can lead to aggression in the context of perceived threat [48]”

Broader Significance quote:

“These results reported here present a challenge to a number of theoretical accounts of religious belief, especially those which emphasize a link between religious and spiritual beliefs and the perception of agency [8, 11, 16, 17, 22]. The present findings put religious and spiritual beliefs in a new light by suggesting that they are not so much linked to the perception of agency as they are broadly to moral concern, and in particular empathic concern. In line with this view, a number of theologians and religious scholars have claimed that compassion is a central theme that unites many religions [117, 118]. While further work is needed to establish causal links, it is plausible both that religious thinking increases moral concern, and that individuals who possess greater levels of moral concern are more inclined to identify with religious and spiritual worldviews.”

Several qualifications there and the whole paper is worth reading in full. For Doug to say this is an overreach “A recent series of experiments validates this idea.” I think the only proper way to validate another’s idea is to address it specifically in a Paper. Claiming it is so, does not make it so. The paper does not assert that analytical thinking is a “flaw” for example.

Doug says: “This raises another interesting point reported by the above paper: There is no reason why we can’t move back and forth between religion and science, between our moral sense and an analytic perspective. ”

The Paper says which I think is very important:

“We suggest that this structural feature of the brain underlies the long noted anecdotal tension between materialistic and spiritual worldviews. This linkage is supported by three observations. First, brain areas implicated in analytic thinking (TPN) support cognitive process essential for maintaining a naturalistic world view (e.g. thinking about objects, mechanisms and causes; [29, 49, 71, 73–77]), whereas the brain areas implicated in moral concern (DMN) are associated with thinking about phenomena which have traditionally been thought of as non-physical, namely minds and emotions [78–83]. Second, brain areas associated with materialism (TPN) tend to be suppressed when brain areas associated with moral concern (DMN) are activated [29, 71, 72]. This might explain the tendency to link mind with spirit, i.e. the view that minds and emotions are associated with the extra- or super- natural. Third, brain areas associated with analytic thinking are associated with religious disbelief [73, 74, 84], and brain areas associated with moral concern are associated with religious belief [73] and prayer [84, 85].”

“The Present Research

“In the studies reported here, we examine the relationship between belief in God and/or a universal spirit and individual difference measures that characterize the domains of cognition of theoretical interest (in particular analytic thinking and moral concern). Numerous findings cited above support the view that increased activity in the TPN and DMN is associated with individual differences in the relevant cognitive domains. However, it is important to note that these findings do not necessitate a negative correlation between individual difference measures of analytic reasoning and moral concern. The neuroimaging findings show there is a constraint on activating both brain networks at the same time. However, tests of empathic concern and of analytic thinking measure people’s ability within specific contexts. Engaging social stimuli are associated with activation of the DMN and deactivation of the TPN, whereas analytic problems are associated with activation of the TPN and deactivation of the DMN. Hence, there is no contradiction inherent in an individual excelling in both domains, provided they engage and disengage the DMN and TPN in a manner appropriate to the context. Indeed, it is plausible that this feature of the brain’s organization is present precisely so that analytic and empathetic thinking do not interfere with each other.”

also that:

“The tension between the brain networks is hypothesized to be behaviorally relevant when people are faced with ambiguous or mixed stimuli, which participants might respond to either by engaging analytic thinking or by engaging empathy. Our claim is that in these ambiguous cases, the balance of the individual’s abilities/tendencies will determine how likely they are to respond by engaging one network rather than the other. Our working hypothesis is that religious and spiritual stimuli provide such an ambiguous context.”

Most of the studies were of the extremes found in ASD and Psychopathy:

“These studies are guided by a theoretical model which focuses on the distinct social and emotional processing deficits associated with autism spectrum disorders (mentalizing) and psychopathy (moral concern). ”

“There is evidence that the deficit in mentalizing associated with ASD and the trait of callous affect seen in psychopathy are distinct. Individuals with psychopathy have normal or better than normal mentalizing abilities [38], a feature which helps explain their ability to manipulate others. Conversely, the ASD phenotype is not generally associated with callous affect, i.e., a deficit in feelings of empathic concern for others [39–41]. The clinical dissociation between ASD and psychopathy is also reflected by a dissociation in the associated traits which is evident in the non-clinical population [33, 42].”

and finally:

“Our theory, the opposing domains hypothesis [24, 29, 30], holds that our neural architecture has evolved in such a way that it creates a tension between analytic thinking and moral concern. This contrasts with Baron-Cohen’s model, which emphasizes a tension between analytic thinking and aspects of social cognition impacted by ASD (i.e. mentalizing). Empirical support for our theory derives primarily from work in neuroimaging. First, reviews of the neuroscience literature, including formal meta-analyses, support the view that these two broad domains (analytic thinking and moral concern) map onto two anatomically discrete cortical networks. The task positive network (TPN) is consistently activated by cognitively demanding non-social tasks, including mathematical, physical and logical reasoning tasks [29, 49–53]. Individual differences in these skills are associated with increased TPN activation during these tasks [52, 54]. The default mode network (DMN) is consistently activated by social and emotional cognition [55, 56]. Our hypothesized broad cognitive category of ‘moral concern’, suggested to us by the personality profile of individuals with psychopathy, maps well onto the known functions of the DMN. Greater activity in the DMN has been associated with more empathic concern [57–59], social connection (i.e. reverse of prejudice and disconnection) [30, 60–65], prosocial behavior [60, 66, 67] and moral reasoning [68–70]. Notably many of these studies link individual differences in these characteristics to DMN activity [57, 59, 60, 66, 67].

Second, it has long been known that the TPN and DMN exhibit an antagonistic relationship, in the sense that activation of one network corresponds with deactivation of the other network below resting baseline. Initially, it was observed that a broad range of cognitively demanding non-social tasks (which we characterize broadly as involving ‘analytic reasoning’) not only activate the TPN but also deactivate the DMN [50, 71]. It was later found that the TPN and DMN also tend to be in tension during ‘spontaneous cognition’, i.e. when the participant is not given any task [72]. This phenomenon is referred to as ‘resting anti-correlation’ between the networks. It suggests that competition between the networks is an emergent property of the network architecture of the brain. Finally, we have demonstrated that attention to engaging social stimuli not only activates the DMN but also deactivates the TPN. In a subsequent study[30] it was shown that this pattern of DMN activation and TPN deactivation was present for humanizing depictions of individuals, whereas dehumanizing depictions, which are associated with decreased moral concern, either involved decreased activity in the DMN or increased activity in the TPN. Taken together, these findings suggest that we are neurologically constrained from simultaneously exercising moral concern and analytic thinking.

We suggest that this structural feature of the brain underlies the long noted anecdotal tension between materialistic and spiritual worldviews. ”

It’s an interesting Paper for sure. I do not see anywhere in the paper that alludes to critical thinking analysis as being a “flaw”. They didn’t really say that “Empathy played hardly any role at all in the religious experience.” That’s an exaggerated generalization of only part of what the paper said.

“The neuroimaging findings show there is a constraint on activating both brain networks at the same time. However, tests of empathic concern and of analytic thinking measure people’s ability within specific contexts. Engaging social stimuli are associated with activation of the DMN and deactivation of the TPN, whereas analytic problems are associated with activation of the TPN and deactivation of the DMN. Hence, there is no contradiction inherent in an individual excelling in both domains, provided they engage and disengage the DMN and TPN in a manner appropriate to the context. Indeed, it is plausible that this feature of the brain’s organization is present precisely so that analytic and empathetic thinking do not interfere with each other.”

“Second, brain areas associated with materialism (TPN) tend to be suppressed when brain areas associated with moral concern (DMN) are activated [29, 71, 72]. This might explain the tendency to link mind with spirit, i.e. the view that minds and emotions are associated with the extra- or super- natural. Third, brain areas associated with analytic thinking are associated with religious disbelief [73, 74, 84], and brain areas associated with moral concern are associated with religious belief [73] and prayer [84, 85].”

“One interpretation of these findings is that analytic thinking decreases belief because it encourages individuals to carefully evaluate data and arguments and/or override certain intuitively appealing beliefs [2, 4, 6].”

” A number of theorists have argued that the tendency to perceive agency and intentionality encourage belief in supernatural agents.”

The Paper can be found here: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0149989#abstract0

So my take away message is that there are two distinct ways of thinking about issues and that one must use one or the other, can cross over from one way of thinking to another, but that depending on the type of person and their own leanings they will favor using one way more than the other way. The paper does not seem to say one way is a better or worse way of looking at issues. There seems to be an unspoken suggestion that using both modes in a balanced way could be a useful conscious choice. However they do not determine whether switching from one mode to the other mode is simple or easy or always a conscious choice being made.

The paper also presented this useful take away message:

“It is important to note that individuals with high levels of moral concern will not necessarily behave more ethically in all situations. Indeed, some researchers have claimed that high levels of empathic concern can be a detriment to moral behavior [47]. Further, there is empirical support for the view that moral concern for others can lead to aggression in the context of perceived threat [48]”

Thanks for posting quotes from the source document. I read the white paper a few times before posting my article, so I’m familiar with it. However, this allows other readers here to see information from the original study.

Now, let’s get to your comments.

First, you say: “For Doug to say this is an overreach “A recent series of experiments validates this idea.” I think the only proper way to validate another’s idea is to address it specifically in a Paper. Claiming it is so, does not make it so. The paper does not assert that analytical thinking is a “flaw” for example.”

In other words, to simply make claims without offering a solid explanation is improper. I agree with your point. However, it doesn’t apply here, since I laid the whole story out in detail in my book, Lenses of Perception.

As I say in the “About” section of this web site, I’m assuming visitors here have read the book, although I do try to offer introductory explanations for newcomers as well.

I agree that if you read this article by itself, without what I’ve presented in the book, it would be a meaningless claim to say the study I am citing is validation.

As for the paper not asserting that analytical thinking is a “flaw,” I agree with you. However, I haven’t asserted this either, nor would I.

I think you might be referring to my article, “The Lens of Science and Its Flaw.” That article, however, doesn’t say that analytical thinking is a flaw. Not at all. It simply points out that there is a flaw in our modern lens of science based on the historical experiences of science. The flaw in the lens makes the world look as if it is completely mechanistic, when in fact this perspective fails to explain most of life.

For example, as I show in my book, this is exactly why physicists haven’t been able to explain quantum behavior or where the laws of nature come from, and biologists haven’t been able to offer a viable theory for how life began.

This doesn’t mean that analytical thinking is, in itself, flawed. It means that it is incomplete. It’s incomplete, to offer another example, because it can’t show us the meaning of religion or spirituality. This research study that I refer in this article says the same thing. That’s why I say it offers validation.

Next, you wrote: “They didn’t really say that ‘Empathy played hardly any role at all in the religious experience.’ That’s an exaggerated generalization of only part of what the paper said.”

I can see why you might come to this conclusion, since it isn’t immediately obvious. The reason is that the authors of this white paper chose to use the term “mentalizing” when referring to what most people call “empathy.” You can see this more clearly if you follow their footnotes and the papers they cite to support their position.

Once you see that this is true, then the first quote you listed above offers exactly the point I was making. They said:

“Using nine different measures of mentalizing, we found no evidence of a relationship between mentalizing and religious or spiritual belief.”

Replace the word “mentalizing” with “empathy” and you will see that the conclusion is quite clear.

The point they are making is that moral concern is different from empathy, and the correlation between religious belief and moral concern is high, but non-existent between empathy and religious belief. This contradicts the popular belief that empathy plays a key role in religion.

This point is clearer if you read the article they cited, “Against Empathy,” to show that this isn’t a new idea. The paper can be found here:

https://bostonreview.net/forum/paul-bloom-against-empathy

It’s an interesting read.

I find the authors use of “mentalizing” to be a poor choice, but I can see why they did this, since there is confusion over the word “empathy,” since it is sometimes related to moral concern, which is how they use it when they say “empathic concern.” However, I think “mentalizing” is by far a worse choice and they would have been better off just explaining what they mean by the word.

They do try to explain, but they are mainly writing to experts, so they didn’t make it clear to non-experts.

I think that answers all of your concerns.

I appreciate the time you took to respond. I agree that the original source paper was valuable to read. It helps to understand the experiments they ran and the conclusions they reached.

I took the same approach in my book, in laying out the research and conclusions. This article, however, was intended for those who read Lenses of Perception first. That’s why your comment is helpful, since it allows me to help fill in some of the gaps to those who haven’t read the book yet.

Thanks.

Doug.