By Doug Marman

The New York Times just ran an opinion piece that is a good example about how articles on neuroscience often get the big issues wrong.

The author, Alex Rosenberg, isn’t ignorant of the topic. He’s a co-director of the Center for the Social and Philosophical Implications of Neuroscience. In other words, he is fully informed of the science of the brain. So, he clearly has every right to state his opinions. Unfortunately, he misses the point badly.

Right from the opening paragraph, Rosenberg misdirects and misrepresents the issue. I don’t mean to say that he is doing this intentionally. I believe he is stating the problem honestly as he sees it. He’s just using the wrong lens.

Here is how he begins: Ever since Plato, philosophers have made it sound like a truism that we know the reality of our own thoughts:

“They have argued that we can secure certainty about at least some very important conclusions, not through empirical inquiry, but by introspection: the existence, immateriality (and maybe immortality) of the soul, the awareness of our own free will, meaning and moral value.”[1]

Rosenberg then goes on to berate two recent authors for continuing with this tradition, as if something that seems so fundamentally true can “trump science.” Not so, he tells us. We might think that we know what’s going on in our own minds, but numerous studies show that this simply isn’t true. We don’t know.

Here’s the first problem with this article: Plato wasn’t talking about knowing our mind. He was talking about knowing our self. He never said that we can ever truly know our own mind our even the true nature of our thoughts. The fundamental truth that Plato and many other philosophers have pointed to is the experience of being conscious.

Using “introspection” to study our thoughts isn’t even in the same ballpark as the experience of consciousness. Experiences are far more fundamental than thoughts.

A lot of neuroscientists mix these up. They do so for a good reason: They are using third-person lenses. In other words, they are taking the traditional scientific approach of viewing the matter as if they are outside observers—as if they are completely outside of the mind or the experience of consciousness and looking in. This is the objective approach, and it has long been used in science for a good reason, because it is excellent at understanding cause-and-effect relationships like we see in mechanisms and chemical reactions.

However, this is the wrong lens to use for understanding the experience of consciousness. If we insist on using a third-person approach, then we have assured our failure to see it at all. The only way to understand the nature of experience is through experience, not by mental analysis.

Trying to understand the mind by thinking about it with the mind is like trying to find reality in a hall of mirrors. Photo by Bjoern Lotz.

We might as well use a telescope to look for microbes in a drop of water. We will see nothing. Even worse, we can fool ourselves into thinking that microbes don’t even exist, because we can’t see them.

We need to use the right lens, the right tool. In this case, the only perspective that works is a “first-person” lens. This is how we experience everything, whether it be a new car, eating lunch with a friend, or our own consciousness. Every experience is a first-person perception.

What does an experience mean? That’s a different story. That’s a question we ask with our minds, as if we could interpret an experience or reduce it down to a thought. As soon as we start thinking about our experiences we’ve left the first-person world behind.

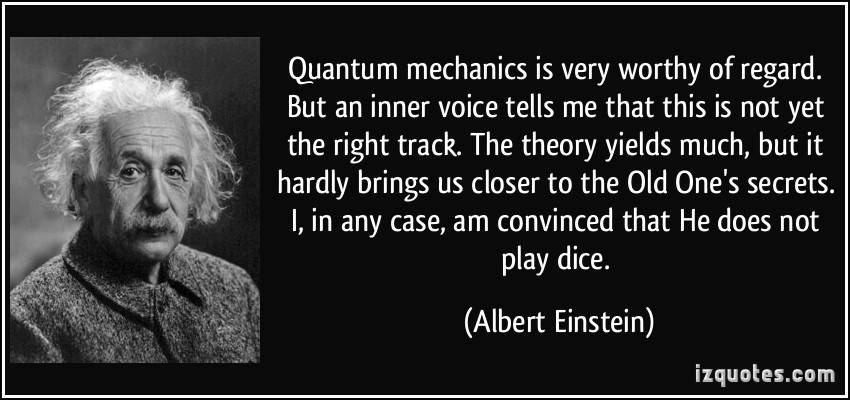

Therefore, the point that Rosenberg is making does not prove that science trumps experience. Quite the opposite. It shows us that science doesn’t understand consciousness. This is exactly why philosopher David Chalmers calls consciousness the hard problem. He writes:

“Consciousness poses the most baffling problems in the science of the mind. There is nothing that we know more intimately than conscious experience, but there is nothing that is harder to explain.”[2]

Third-person lenses don’t work because they move us outside the world of experience. Outsiders can’t see consciousness. This is why we need to use a first-person lens. Chalmers says the same thing:

“If one takes the third-person perspective on oneself—viewing oneself from the outside, so to speak—these reactions and abilities are no doubt the main focus of what one sees. But the hard problem is about explaining the view from the first-person perspective.”[3]

Unfortunately, this isn’t the only problem with Rosenberg’s article. In his zeal to show how much scientific evidence there is that we don’t know our mind, he makes some rather serious blunders. He writes:

“In fact, controlled experiments in cognitive science, neuroimaging and social psychology have repeatedly shown how wrong we can be about our real motivations, the justification of firmly held beliefs and the accuracy of our sensory equipment. This trend began even before the work of psychologists such as Benjamin Libet, who showed that the conscious feeling of willing an act actually occurs after the brain process that brings about the act—a result replicated and refined hundreds of times since his original discovery in the 1980s.”

The first sentence in the above paragraph is right. Subconscious influences affect our choices and decisions all the time. We often try to “explain” our behavior as if it is rational, when, in fact, our subconscious colors everything we do. So, the point Rosenberg is making—that we don’t fully know our own minds—is right.

It’s the second sentence that is the problem. Benjamin Libet did not show “that the conscious feeling of willing an act actually occurs after the brain process that brings about the act…” And no other experiment has proven this either. It is easy to show why Rosenberg is just plain wrong about this. Here is how I explained it in my book,

“None of the experiments show the brain making a decision before the person did. Scientists can’t prove such a claim, since they have no way of determining when a choice is made. Decision-making is a subjective process. They can’t observe it scientifically. No instrument can measure the act of choosing. They can only detect outer activity in the brain, not the inner content of consciousness.”[4]

In fact, not only is Rosenberg wrong about what Libet’s experiment shows us, there are quite a few experiments that contradict his conclusion and one shows clearly that he is wrong. In that case, the “readiness potential” brain signals that Libet detected show up whether a person decides to do something or not, so they can’t be an indicator of a decision being made:

“Judy Trevena and Jeff Miller, psychologists from New Zealand, asked a group of subjects to press a key every time they heard a tone. A second group was told to do the same thing—press a key on a computer after a tone sounds—but only half of the time. It was their choice when to push the button and when not to.

“It didn’t matter whether the subjects in the second group pressed the key or not, the same readiness potential signals were detected. This is proof that this brain activity is not the same as a conscious decision. In fact, it suggests that the term ‘readiness potential’ was right all along. The brain is simply getting ready to act.”[5]

Rosenberg makes the matter worse. He goes on to say: “there is compelling evidence” that our own self-awareness is simply our brain trying to guess at what we ourselves might be thinking. This is a misrepresentation. I’m giving Rosenberg the benefit of the doubt when I say this.

If you interpret “self-awareness” the way I do, as the experience of our own consciousness, then Rosenberg is flat out wrong. But I think what Rosenberg is getting at here is that we often guess about our own behavior and our intentions, the same way we guess at the intentions of others. He is absolutely right about that, but this is not the basis of our self-awareness.

If Rosenberg limited his conclusion to the ideas that we form about ourselves and the picture we might have of who we are, then I would agree with him. But that isn’t self-awareness. That’s our ego he is talking about—the image we have about who we are and how we fit in the world.

Self-awareness is something we gain through the direct experience of our consciousness. No thought involved. No guesswork. It is purely an experience—not an interpretation. That’s what makes this an issue that “trumps science.” Science can’t crack that nut, but we can prove to ourselves the reality of it through our own awareness.

Then Rosenberg really does it. He makes an absolutely ridiculous statement that has no scientific foundation at all, while acting as if it is shored up by empirical evidence. He writes:

“The upshot of all these discoveries is deeply significant, not just for philosophy, but for us as human beings: There is no first-person point of view.”

Here is the logic that Rosenberg just used to arrive at this conclusion: If you first decide to use a third-person lens, and only a third-person lens, to study the problem, then you will discover that first-person perception doesn’t exit.

Well of course it doesn’t exist if you use a lens that requires you to be an outsider looking in. How could you ever experience consciousness that way? How could you ever experience anything?

What’s the real upshot of all this? Science can’t see, detect, measure, or photograph the experience of consciousness. So, what do some scientists do? Well, they make up a story as if they understood the mind well enough to know that it is just making up the experience of consciousness. In other words, they are doing exactly what Rosenberg was telling us the mind does: guessing at the things it doesn’t understand.

If Rosenberg is right that we can’t know our mind through introspection, and I agree with him on this, then how could anyone ever come to the conclusion that the mind is fabricating the experience of consciousness? That makes no sense.

If a person is smart enough to make such a statement, why wouldn’t they be smart enough to realize that the only way it could be true is if they really did understand their mind?

It baffles me. I don’t have the answer to this question, but if you do, please explain it to me. I really would like to know.

[1] Alex Rosenberg, “Why You Don’t Know Your Own Mind,” The New York Times, July, 18, 2016.

[2] David J. Chalmers, “Facing up to the Problem of Consciousness,” Journal of Consciousness Studies 2, no. 3 (1995), p. 200. Also posted on http://consc.net/papers/facing.pdf.

[3] David J. Chalmers, “Moving Forward on the Problem of Consciousness,” Journal of Consciousness Studies 4, no. 1 (1997), p. 3–46, Section 2.2. Also posted on http://consc.net/papers/ moving.html.

[4] Doug Marman, Lenses of Perception: A Surprising New Look at the Origin of Life, the Laws of Nature, and Our Universe (Washington: Lenses of Perception Press, 2016), p. 277.

[5] Ibid., p. 278-281.